Part 1: Rapid testing of blade bearings – but how?

Back in 2013, the Fraunhofer IWES was still only a fairly small Fraunhofer institute and many of the test benches which would later shape the image of the institute were still only to be found in the minds of the first employees. The rotor blade tests were already delivering reliable results, but our expertise in other areas was still rather limited. Nevertheless, a manufacturer of blade bearings approached us to propose a joint research project. Blade bearings connect rotor blades with rotor hubs, and it is thanks to them that the rotor blade can turn around its own axis, thereby controlling the performance of the system. Rotor blade bearings had given us relatively little cause for concern since the days of Growian, but some new developments were emerging with effects that were difficult to estimate.

Not only were the bearings becoming larger and larger with every new generation of turbines – and simultaneously straying further and further away from the established dimensions for rolling bearings up until that point – there were also another two new design aspects with effects that were difficult to estimate at that time: On the one hand, the use of individual control of blades for load reduction, which is associated with a different bearing operating mode and, on the other hand, the higher loads resulted in the desire to switch to three-row roller bearings instead of the usual four-point bearings.

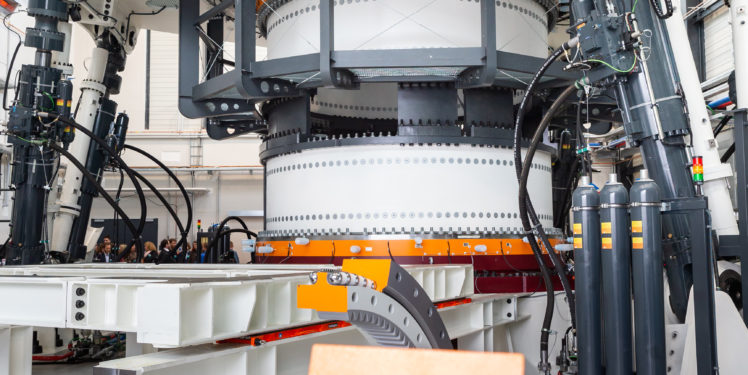

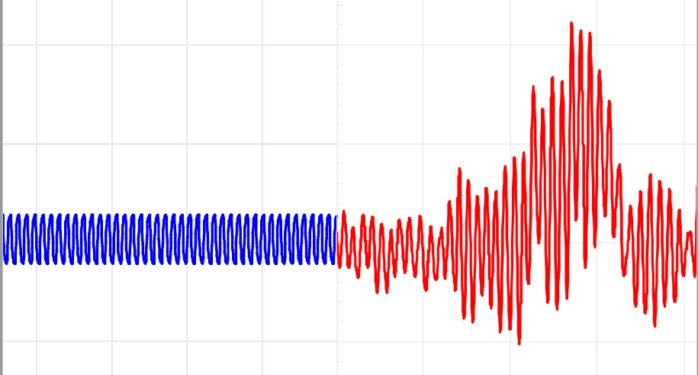

IMO suggested to IWES to perform realistic tests to determine the extent to which these developments could pose a risk. Such tests should not take too long, as they would need to be completed between production of the first blade bearings and the beginning of series production. At this point, we already knew some things about large test benches, but rolling bearings were new territory for us. We found a great partner to support us in the Institute for Machine Construction and Tribology (IMKT) at the Leibniz University Hannover. Essentially, it was known at that time that blade bearings oscillate – in other words, they do not turn continuously, but rather move back and forth. That is practical for a wind turbine, but not so much so for a rolling bearing, as it favors constant rotation. Now we had these unfavorable oscillations, and they were additionally altered considerably by the new load reduction mechanisms. In order to discover how we could test something like that in an accelerated fatigue test, we first had to understand the possible damage mechanisms. However, the available literature on blade bearing damage was practically non-existent (with the exception of a few anecdotal mentions). There was quite a lot of research available on the topic of the “wear of oscillating rolling bearings”, although only considerably smaller bearings had been tested, and that always with constant oscillation amplitudes. The blue line on the graph shows this kind of movement profile. However, blade bearings were operated differently, with constantly changing amplitudes and mean values, as shown by the red line:

I summarized the comparison between the current state of research and the blade bearings in a contribution to a tribology conference in Göttingen, Germany, in 2014. The first approach for a test program resulted from this stage of my research: we take all the movements which are known to be critical and test them directly one after another. At the same time, we apply the loads that a blade bearing experiences in the turbine and simulate the interfaces – in other words, the rotor blade and rotor hub.

At that point in time, we did not know how long a test of that type would take, how much energy it would require, and how precisely the behavior of the interfaces could be mapped. Without a research project, there was no possibility of these ideas maturing, but if we were going to realize a research project, we had to commit to some figures: we submitted a project proposal for a funding application in mid-2013.

More information here:

Part 2: Rapid testing of blade bearings – from the desk to the test bench

Part 3: Rapid testing of blade bearings – The first endurance run